Allied servicemen who found themselves in German prisoner of war camps risked serious consequences if they broke the rules.

Heroic escape efforts as immortalised by big screen adventures such as The Great Escape were not the only infractions of camp rules that could put the prisoners in real danger if caught in the act.

Possessing a radio, even if it was used only for receiving foreign broadcasts, was not tolerated by the German captors.

Now, a home-made wireless crafted in secret by a Wharfedale army officer, and his tale of life in a German PoW camp, has taken pride of place in a war museum’s exhibition telling the true story of prisoners of war.

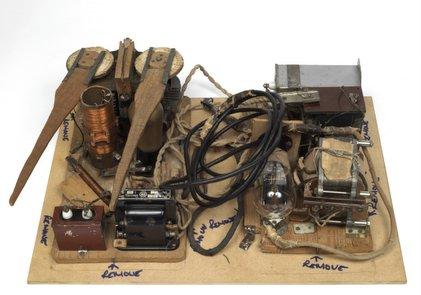

Captain Ernest Shackleton’s ingenious radio, made from old cinema gear, cocoa tins, toilet roll centres and knitting needles, gave some of the men in Oflag 9 AZ, Rotenburg an der Fulda, a chance to hear BBC broadcasts of the Allied progress in the war.

The radio, and Capt Shackleton’s story are featured in the Captured exhibition at the Imperial War Museum North, in Manchester. The show is the first major exhibition held by the museum on the subject of PoWs and their survival in often harsh conditions.

Possessing, let alone using, the radio put the prisoners in danger if they were discovered, and they had some close calls.

The son of Mr and Mrs Frank Shackleton, of Bolling Road, Ben Rhydding, Ernest Shackleton was an expert in wireless research. Educated at Ilkley Grammar School, he studied engineering at Leeds University from 1921 to 1925.

He had a transmitting licence for a ‘remarkably’ equipped radio station set up in his own home, and in 1939 he was awarded the Wortley-Talbot cup for his contribution to the T&R Bulletin, the magazine of the Radio Society of Great Britain.

Serving with the Royal Signals, he was captured by the German army with the 51st Division at St Valery-en-Caux, Normandy, in 1940, and slightly wounded.

He and other officers bought some cinema gear – with permission from the Germans – while at a camp in Warburg. Thanks to having a German sentry present at all times, however, they were unable to use the equipment to make their own radio.

It was after the officers’ move to Rotenburg that Capt Shackleton really got to work on his wireless.

In an interview with the Ilkley Gazette in October, 1945, he said: “The spindles were made from clinical thermometer cases; the plates were made from Rowntree’s cocoa tins rolled out flat on a table with a beer bottle, and two celluloid tooth brush handles formed the insulation for each condenser.

“Valve holders were made from a Bakelite ash tray laboriously cut and drilled with a penknife, the contacts being Rowntree’s cocoa rubs. We found their tins just the right size.”

Wax-impregnated cardboard tubes from toilet rolls also joined the scrapheap challenge, and soon the officers had a receiver capable of picking up BBC news broadcasts.

Late in the war, the prisoners managed to explore off-limits parts of the camp, where they found more useful spare parts from a small ventilating fan and began constructing an AC generator.

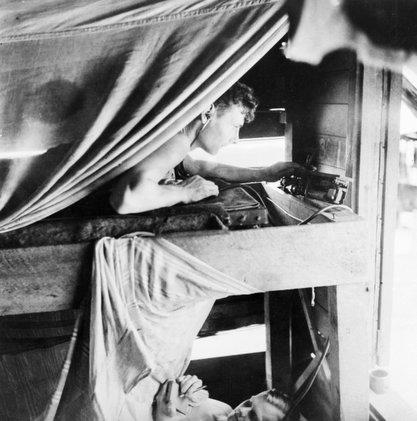

The men worked out a complex warning system for signalling to each other, to give them enough precious seconds to hide their radio should a guard appear. Prisoners who spotted one approaching would ‘saunter away’, sparking a second sentry to do the same, signalling a man outside the room where the radio was being operated to enter the room, warning the men inside to hide the equipment.

The system meant the guards did not get wind that the British servicemen were up to no good. The radio could be hidden in ten to 12 seconds, they found in a ‘dress rehearsal’ timed with stopwatches.

After one particularly intensive search by camp guards, the prisoners were forced to moved the radio to their dining area. It looked like the game was up – half of the set was discovered.

However, the Germans took no action other than putting up ‘the usual’ warning notices, according to Capt Shackleton.

The wireless was cunningly built into the wall behind the false side of a cupboard in the dining area.

On another occasion, early in 1945, the Gestapo sprung a surprise visit on the camp and spent a whole day searching it.

One of the British prisoners saw Gestapo officers attempting to crowbar their way into the sturdy hide where the equipment was concealed, and failing.

In his 1945 interview, Capt Shackleton said: “This officer said it was the worst five minutes he had ever spent, for he knew that if the set had been found there would have been serious trouble.

“It says much for the ingenuity of the squad of officers who designed and built this “hide” that it should withstand an intensive Gestapo search and yet remain in working order.”

The prisoners of war used the hidden wireless to listen to news broadcasts. They tried to receive BBC news broadcasts, but when the signal faded at certain times of the year they tuned into an American programme, or transmissions in German. Those who took down the news had to be fluent German speakers.

Receiving broadcasts was not the only intention for Capt Shackleton’s wireless set, however.

As the men realised there were possibilities of the camp being captured by advancing Allied forces in the summer of 1944, they considered a much more dangerous course of action – transmitting their own messages to Allied troops.

The men found ‘talkie’ gear’ among the remaining cinema equipment that could be used to assemble a transmitter. There were huge risks, however.

The German guard and camp officers lived in the same building as the prisoners, and it was not known if there was any short-wave receiver that might pick up the messages they were trying to transmit. The transmitter could have been constructed within 48 hours of orders from the British camp authorities.

As Nazi Germany began to crumble under the Allied offensive, the men found the supply of electricity harder to come by. Again, some technical ingenuity came to the rescue – with the aid of more of the ever-useful cocoa tins – and they tapped power from German cables passing under the British quarters.

There was always a big risk of shorting the German power supply and giving themselves away. “It can be gathered from this that the taking of the news in a German camp was exciting, to say the least, as one false step would have been more than disastrous,” said Capt Shackleton in his 1945 interview. “The apparatus would have been confiscated, and readers can imagine what would have happened to the operators had they been caught.”

The radio was abandoned but Capt Shackleton returned to Germany and, with the help of American occupying forces, recovered his radio, donating it to the British authorities as a museum piece.

After the liberation of the prisoners, Capt Shackleton returned to Ilkley in April 1945, a little thin, but in otherwise perfect health, describing his food in the camp as good, and rations similar to those given out to German civilians.

- The exhibition runs at the museum until January 3 2010.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here