MANY of our Christmas traditions trace their roots back to the Victorian era - and cosy family images of that time have become synonymous with the festive season.

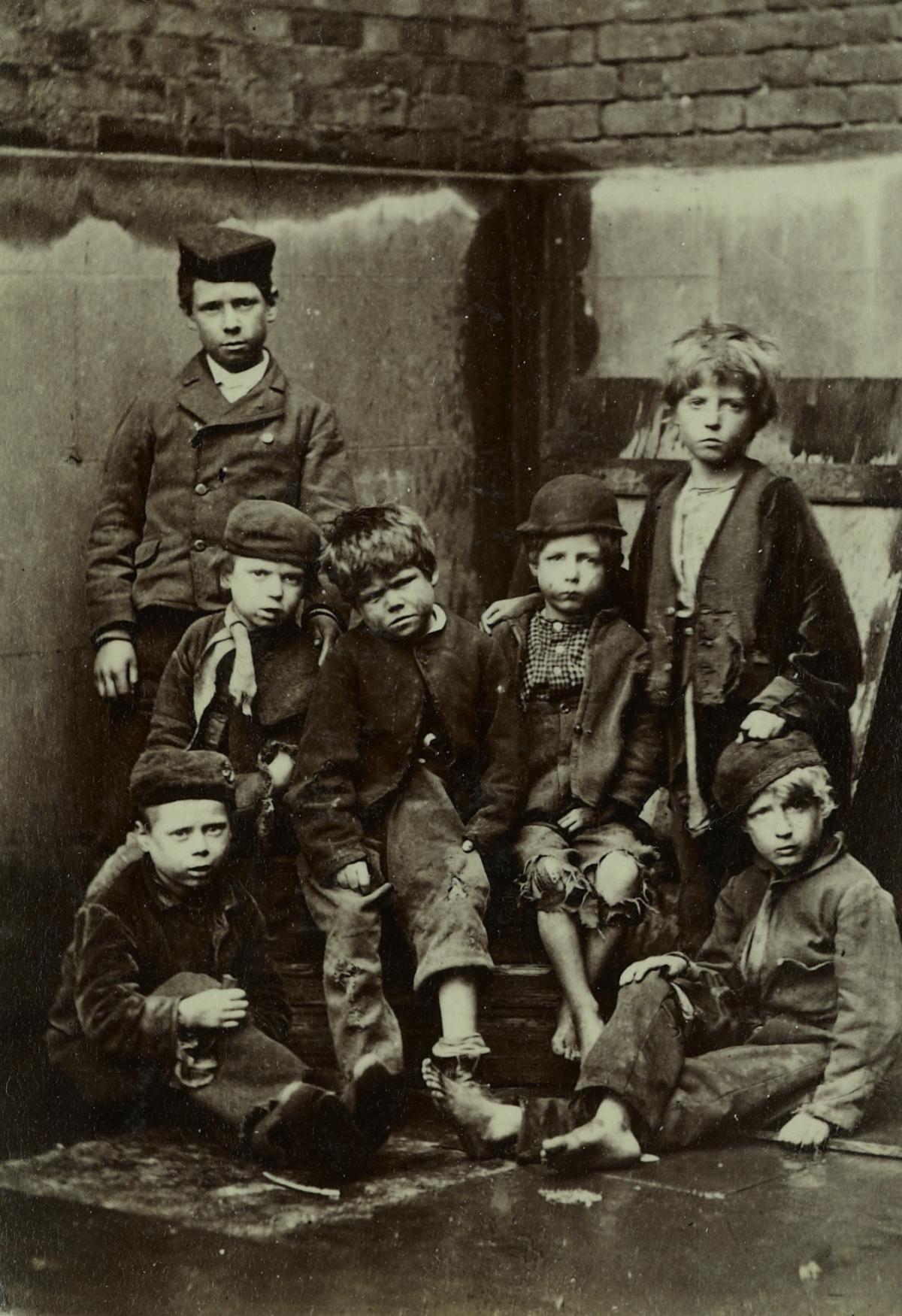

But the reality was very different for countless poverty stricken children living in Victorian England. For them Christmas can have been no more than a brief respite from lives of unrelenting misery.

Childhood destitution was shockingly widespread during the 19th Century and in 1893 the Ilkley Gazette described well-attended lectures and fund-raising events which took place throughout Wharfedale and Aireborough to raise money and support for Dr Barnardo. His homes were taking in the “waifs and strays” described by the Ilkley Gazette as the “outcast children of our great cities and towns.”

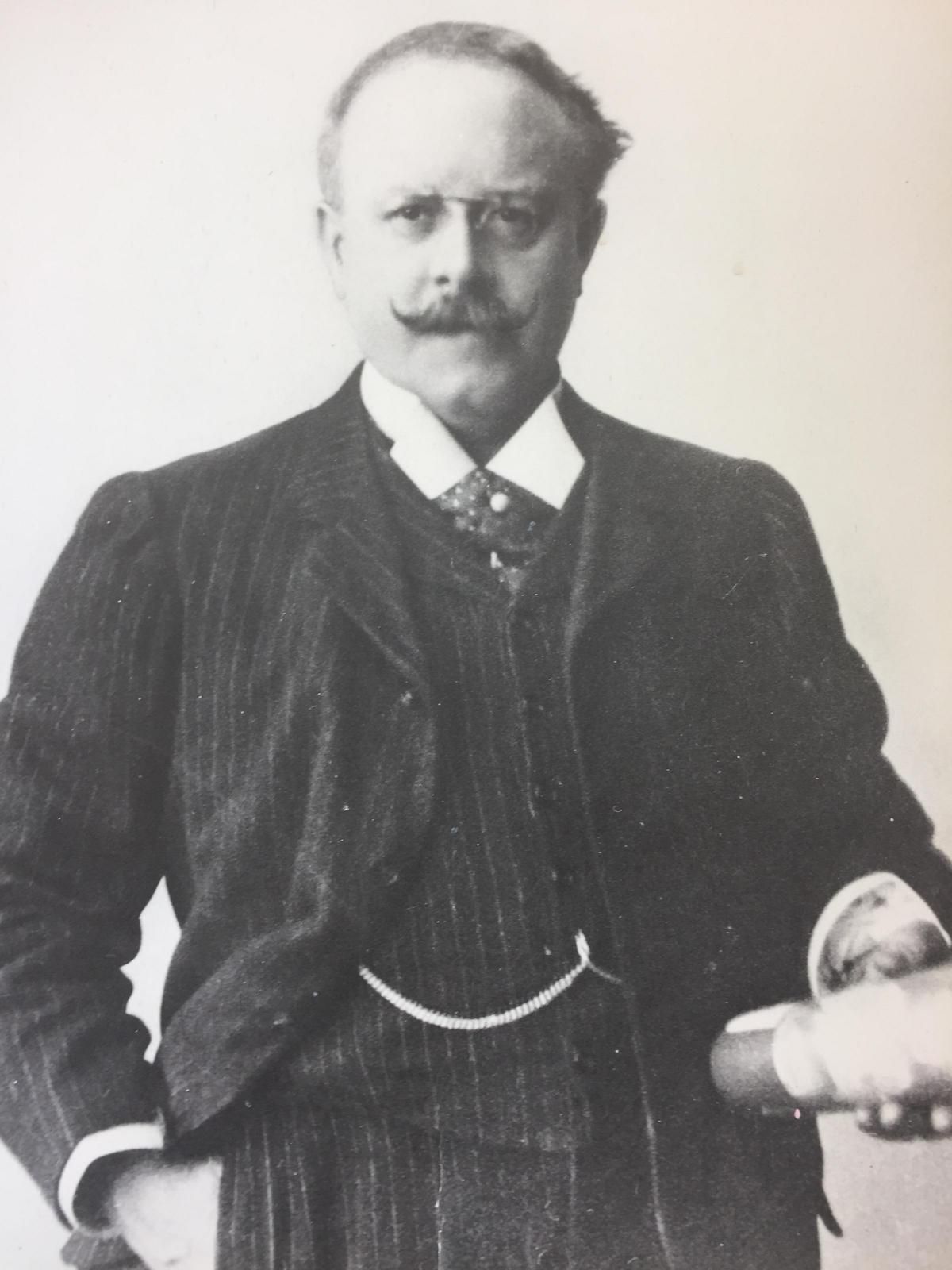

Born in Dublin in 1845 Thomas John Barnardo encountered terrible childhood deprivation when he moved to London to train as a doctor.

He set up a ‘ragged school’ in 1867, and was so moved by the poverty he saw in the East End that he decided to abandon his medical training and devote himself to helping the children who had nothing.

In 1870, he opened his first home for boys, giving the youngsters shelter and training in a trade.

The Barnardo’s charity website says: “To begin with, there was a limit to the number of boys who could stay there. But when an 11-year-old boy was found dead — of malnutrition and exposure — two days after being told the shelter was full, Barnardo vowed never to turn another child away.”

It adds: “By the time he died in 1905, the charity had 96 homes caring for more than 8,500 vulnerable children.”

Announcing a bazaar to raise funds for Dr Barnardo’s work in 1893 the Gazette described his homes as “those most deserving of institutions.”

For the poorest children in society - even those with homes and families - life could be desperately hard in both the 18th and 19th centuries.

As the industrial revolution brought about rapid changes in society children as young as four were forced to work long hours in appalling conditions, with accidents only too common - some resulting in death.

In February 1824 the death of a child miner at Rawdon colliery was recorded in a short paragraph in a local newspaper.

The piece, from the British Newspaper Archive, said: “On Tuesday last a melancholy circumstance took place at Rawdon colliery. A boy of the name of J Spence, about eight years of age, was attempting to get out of a corf (basket) at the pit before his companion when his foot unfortunately slipped and he was precipitated to the bottom of the pit and killed.”

Writing about the plight of these children, Christine Lovedale, from Aireborough Historical Society, said: “As in other early industries child labour was used, it was cheap and in coal mines a small child could manoeuvre into spaces inaccessible to an adult.

“They were often working for 12 hours or more in horrific, filthy, wet conditions with little or no light.

“The 1842 Mines Act forbade the employment of women and boys under the age of 10 in mines, it was not until 1900 that boys under the age of 13 were not allowed to work or be in an underground mine.”

“Child labour was also commonplace in the mills and mines of the 18th and 19th Century where they worked for long hours in often hazardous conditions.”

She added: “A scandalous aspect of mill life was the employment of pauper apprentices, young children who were orphaned or in dire circumstances and dependent upon the Parish for their welfare were apprenticed to mill owners, often a considerable distance from their homes thus relieving the Parish of responsibility for them.

“The conditions these children endured, some as young as four years old, were shocking.

“Poorly fed, clad in rags and working interminably long hours their situation was intolerable.”

In 1802 Prime Minister Robert Peel introduced the Pauper Apprentices Act, which stipulated no working at night, and which set a 12 hour limit on the working day.

In 1833 legislation was brought in to stop children under nine being employed. Children aged between nine and 13 were to only work eight hours per day, with two hours taken out for education. Young people aged between 14 and 18 were allowed to work a maximum of 12 hours.

In1844 safety legislation was introduced so that all moving machinery was fenced and no cleaning of machinery or parts was allowed when the machinery was in motion.

Factories Inspectors were appointed and prosecutions followed for those in breach of the act.

In 1845 a number of Yeadon mill owners were fined after committing offences in breach of the Factories Act.

Among those prosecuted Dennison, Teale and Co of Yeadon were fined £1 for employing a child in their mill in the morning and afternoon of the same day. James Hudson of Guiseley was also fined for the same offence. Mark Robinson of Guiseley received a heftier penalty of £5 for failing to have the main gearing in his mill securely fenced

Among the archives is an undated, statement from Hannah Brown - who had started work at the age of nine - describing conditions in an Otley mill where she had worked for 14 hours a day without a break and where children were punished for becoming tired.

Additional research was carried out by Edwy Harling, from Aireborough Historical Society, looking at the British Newspaper Archive.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here