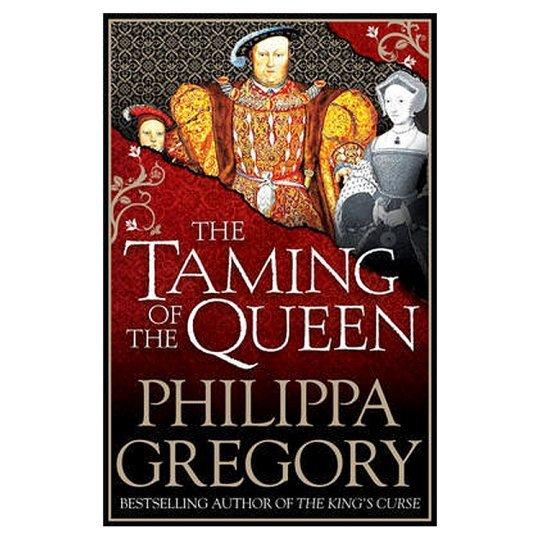

Ruth Hobley reviews Philippa Gregory's latest paperback, The Taming of the Queen, published by Simon and Schuster at £7.99.

THE image of Henry VIII as the serial husband is one so thoroughly embedded in the British imagination that it has become at worst a hackneyed cliché and at best mildly amusing. Nowadays, the six wives provide little more than an opportunity for primary school girls to play dress-up during history lessons, with the ensuing arguments over which unlucky participant will be lumbered with Anne of Cleves.

The one most likely to be forgotten in such games is Catherine Parr. It is notable and perhaps uncomfortably telling that, of the two queens whose fates are unique within the notorious rhyme, popular imagination has continually emphasised the one who ‘died’, rather than the one who ‘survived’ (you won’t find Catherine Parr in the role of Dr Quinn, Medicine Woman). Philippa Gregory’s latest novel is therefore doubly fascinating, both for its emphasis upon a largely neglected Tudor queen, and for the way in which it demonstrates the lengths that a medieval woman had to go to in the midst of a tyrannically male-dominated society simply to stay alive.

For Gregory’s Kateryn Parr (she opts for the queen’s own spelling), the years of her marriage to the king of England are primarily a period to be endured, rather than the defining moment of her existence. Twice widowed herself, she is a woman with a life and a mind of her own, regardless of who her husband currently happens to be. Hence the (slightly anachronistic) title: in the eyes of the king, and many men of the Tudor court, Kateryn is not the docile nurse or humble servant that convention would have her, but an independent-minded widow-turned-queen whose impetuous spirit and dangerously radical thinking must be curbed. And the lengths that those in precarious positions of power will go to in order to silence such dissenters are truly shocking.

At times Gregory is a little heavy-handed in her efforts to get her point across. There are probably more subtle methods of demonstrating a protagonist’s courage, scholarship and pride than having her essentially announce these attributes to the reader, and there are also some strange moments in the writing which see medieval dialect juxtaposed with modern-day colloquialisms that can be a little jarring. Incidentally, I would also advise readers against searching for images of Gregory’s dashing Thomas Seymour on the internet, unless they are prepared for some severely bearded disappointment.

That being said, The Taming of the Queen is highly valuable for the way in which it shows how history has silenced, and frequently continues to silence, its women. By turning them into amusing nursery rhymes and cut-out types (the witch, the saint, the whore) to be coloured in with felt-tip pens by schoolchildren along with the jewels on the king’s crown, we are taught to forget that these were real women, real people, who thought, spoke, and struggled to survive on a daily basis. In Kateryn Parr, however, Gregory shows us a woman who not only ‘survived’, but lived.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here