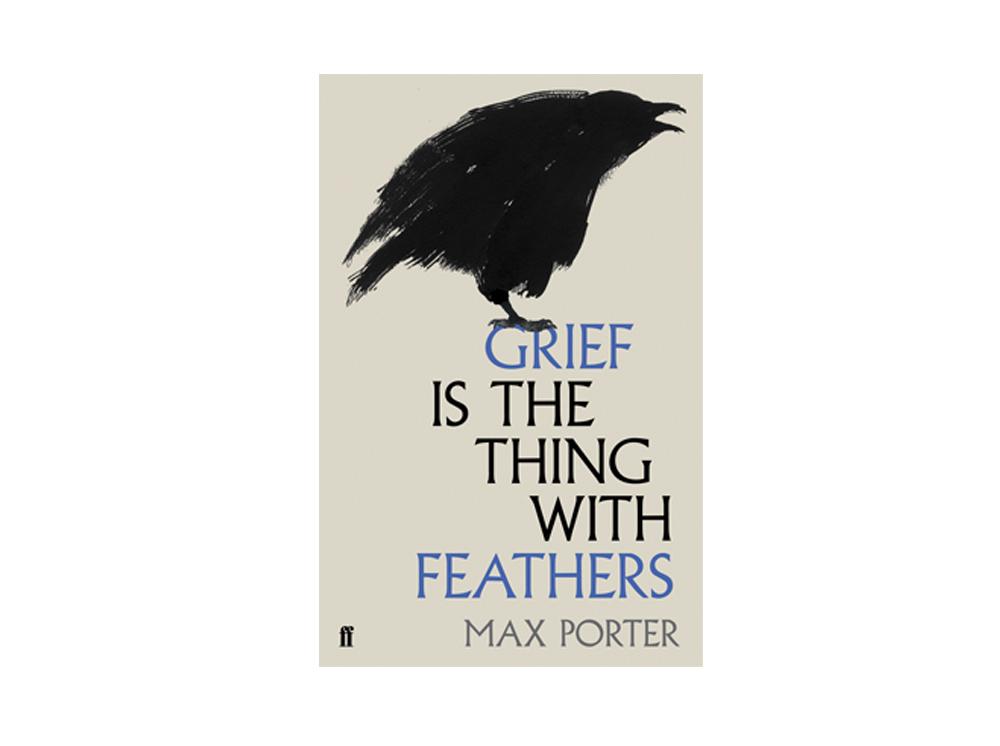

Grief is the Thing with Feathers by Max Porter

Review by Ruth Hobley

As an object, this is a curious Tardis of a book. Despite its diminutive size, generous printing, and imperceptibly brisk pace (savouring it requires a remarkable amount of self-control), Max Porter somehow manages to pack his first book with the essence of a life, a family, and every ripple that ricochets out from the centre of loss. It’s an extraordinary achievement.

This pocket-size hybrid of novella, fable and poetry collection is divided across three perspectives, but the shadow that is cast over the whole is resolutely bird-shaped. There is little to be said as far as plot is concerned that cannot be gleaned from the cover: the death of a wife, and mother, which heralds the arrival of a hulking black crow. So far, so Edgar Allan Poe. But this crow is a different beast, having hopped, scrabbled and clawed his way straight out of Ted Hughes’ Crow (Porter’s protagonist, if that is the right word, is a Hughes scholar), and bringing with him all of the despair, antagonism and wit, with an extra helping of foul language, that Hughes’ Crow is renowned for.

Crows and grief, crows and bad things in general it would seem, have gone together like bacon and eggs (if not quite so pleasingly, and if the eggs were in fact a physical manifestation of the bacon) since time immemorial. And yet Porter’s project feels wholly fresh and unflinchingly raw, and you don’t need to have a whole murder of literary crows at your beck and call to appreciate it. This is an ancient, and yet thoroughly modern Crow, and there is often the sense when reading (in a way which is uncanny, rather than cliché) that we have encountered him before. After all, as Crow well knows, grief is not new to the world, or to books, only to individuals; and the sorrow of this family is portrayed with startling and arresting clarity.

Porter’s book is so intensely moving at times precisely because at others it is so flippant; it is as funny and clever, not to mention as life-affirming, as it is cynical and sad. Each time the writing feels as though it is in danger of lapsing into the anaesthetic lull of platitudes, one or another of the multiple perspectives emerges to pull it in a slightly unexpected direction, gently nudging the overly complacent reader in the ribs as it does so (‘Eugh, said Crow, you sound like a fridge magnet’).

If I tried to even summarise everything that this book has to offer here, my review would most likely finish up longer than the book itself, and even at a mere 114 pages, that’s still more review than anyone wants or needs. Suffice to say, it is a book worth reading (it won’t take long!), and one which will stay with you, not just as a memory, but as a kind of rhythm. Perhaps because it is not quite poetry and not quite prose, it filters into the pattern and pace of your thoughts (I suppose this is what another reviewer meant when describing it as a ‘living thing’, because it does seem almost to breathe for itself), and when I reached the end I found myself turning over the blank pages at the back in the hope of one more word.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here