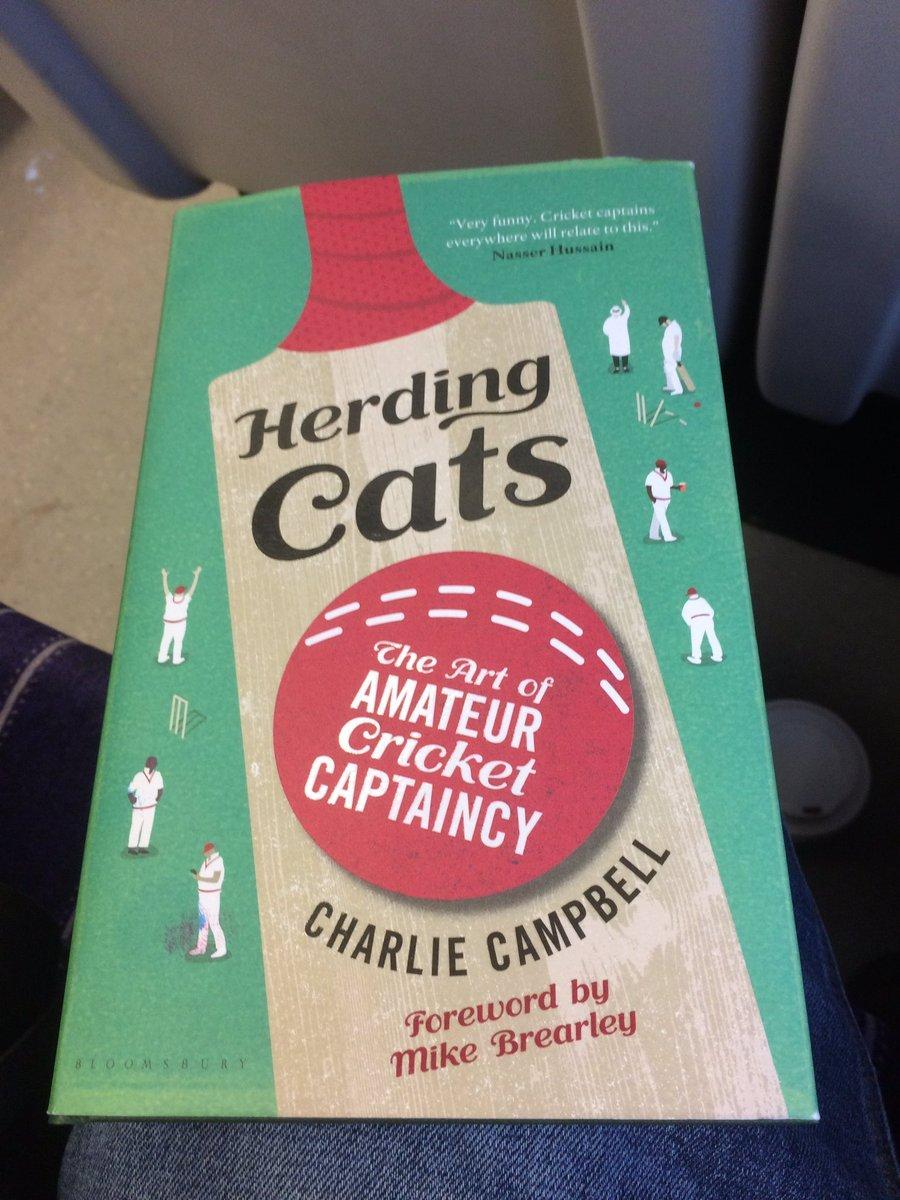

Herding Cats –The Art of Amateur Cricket Captaincy by Charlie Campbell

Reviewed by Mike Sansbury of The Grove Bookshop

THE psychoanalyst and former England cricketer Mike Brearley, one of our most thoughtful and successful captains, wrote a classic book called The Art of Captaincy, in which he examined the qualities needed to make vital decisions at cricket’s highest level. It makes valuable reading for anyone in a position of leadership, providing insight into getting the best out of people, forming strategy and achieving success, but just how relevant is it to those of us who spend our summers trying to drag reluctant forty-somethings onto a cricket pitch? As captain of the redoubtable Authors’ Cricket Club, Charlie Campbell has attempted to rewrite Brearley’s masterly guide for those of us at the foot of the cricket ladder, and the result is illuminating and entertaining in equal measure.

A Test captain these days has a team of analysts, coaches and psychologists helping him at every turn, and apart from media duties his primary job is to manoeuvre his players into a position of superiority, culminating in victory. The amateur, however, will have spent the days leading up to a game frantically trying to assemble a team, book the pitch, collect supplies for tea and send out directions so that there is a reasonable chance of at least ten players getting to the right ground before the game starts. It’s hard to imagine current England captain Joe Root looking at his watch and announcing, “We’ll give it another ten minutes, and if nobody else turns up we’ll have to bat.”

Clearly there are some huge differences between the amateur and professional set-ups, but there are many similarities too. Even at the very lowest level, egos need to be massaged. Some players perform better under pressure, while others need continual reassurance; the only difference is that where Brearley had to deal with Ian Botham and Bob Willis, we at the social end of the scale are faced with the vicar running late after evensong or the businessman missing a train. Social cricket might seem more light-hearted but its importance to the participants shouldn’t be underestimated. After a hard week at work it can be hugely satisfying to take the field in the company of friends. It’s about camaraderie more than team spirit after all.

Campbell is brilliant at highlighting the similarities and differences between cricket’s highest and lowest forms. He deals with such issues as practice, ability levels, field placing and even touring (the Authors’ XI have played in India and, somewhat implausibly, Vatican City), but what struck a chord with me more than anything else in this book was his pinpointing of what makes cricket at this level so ultimately rewarding. Cricket is often referred to as a team game for individuals, in which everyone has a chance to shine. Each player is likely to bat, everyone fields and, at our level, most players will get an opportunity to bowl too. Depending on how successfully this goes, it can be a rather depressing experience, but on those rare days when everything clicks, when the nervous fielder pulls off a sharp catch, the occasional bowler finds his line, the reluctant batsman hits out and the team really comes together, it gives everyone a tiny glimpse of what Brearley and company must have felt at their peak. Every amateur cricketer should read this book.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here